Haddon in the Straits, barefoot.

Some Manner of Self-Realization (for A. C. Haddon)

2012

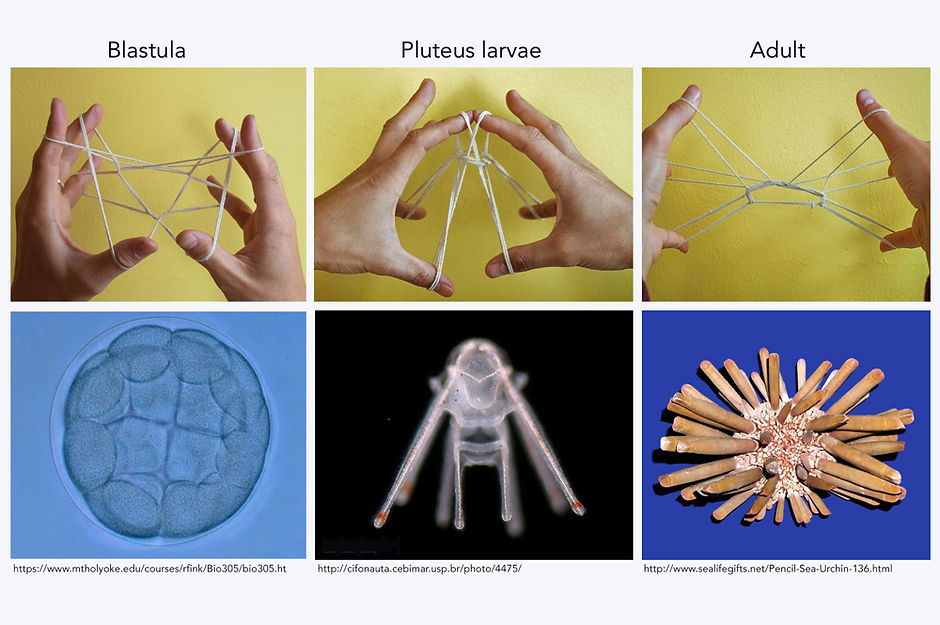

From a single egg a creature begins its process of making through growth, involution, re-inscription. Sea urchins are one of these most intensively studied creatures in biology. We are close relatives to them, so their early development as embryos can work as models of our own. But after a certain point they do things that are only theirs' to do: A floating glassy hollow ball turns into a winged spacecraft, and then a dense pile of opaque spines resting on an ocean's floor.

String figures are about orchestrating form of formlessness through indefinite permutations of the same material. The figures are developmental algorithms that can spontaneously fail, or other times they mutate into something new. Inherent to them is a system of genetics for passing down their shape from one set of hands to another, and yet another, emerging into form as they might in the fingery milieu of a specific set of hands. In string figures and the developmental dynamics of the sea urchin alike we can see how process as is end in itself.

On the left are three key stages within a twelve-step sequence of string figuring that leads not simply to a final form, but through the acrobatic choreography of metamorphosis in a seas urchin, egg to adult.

I adapted this sequence from a traditional string figure called "the sunset" that originated from the deep cultural tradition of inhabitants of the Torres Straits. Within those cultures, string figures had been a significant, embodied aesthetic form. The Torres Straits have been of biological, anthropological - as well as literary and imaginary - interest for a long while. Indeed, Chapter 20 of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea is devoted to the Torres Straits. The narrator of the story, Professor Pierre Aronnax reports at one point during an expedition that:

"Among mollusks and zoophytes, I found in our trawl's meshes various species of alcyonarian coral, sea urchins, hammer shells, spurred–star shells, wentletrap snails, horn shells, glass snails."

ALFRED C. HADDON, who was the first Westerner to document the string figures of the Torres, was first drawn to that region to study its marine biology, not to do anthropology. He was an embryologist, studying the early development of creatures like the sea urchin. However, as Haddon reports in the opening lines of his "The Ethnography of the Western Tribe of Torres Straits" (1890) :

"In the summer of 1888 I went to Torres Straits to investigate the structure and fauna of the coral reefs of that district. Very soon after my arrival in the Straits I found that the natives of the islands had of late years been greatly reduced in number, and that, with the exception of but one or two individuals, none of the white residents knew anything about the customs of the natives, and not a single person cared about them personally."

"When I began to question the natives I discovered that the young men had a very imperfect acquaintance with the old habits and beliefs, and that only from the older men was reliable information to be obtained. So it was made clear to me that if I neglected to avail myself of the present opportunity of collecting, information on the ethnography of the islanders, it was extremely probable that that knowledge would never be gleaned - for if no one interested himself in the matter meanwhile, it was almost certain that no trustworthy information could be collected in, say, ten years' time."

Haddon, in the 140 page monograph, goes on to describe the practice of string figuring:

"Womar, or Womer, a string game allied to our "Cat's Cradle," is played by children and sometimes by adults. I have seen it played at Muralug, Tud, and Mabuiag. The game was universally played throughout the Straits, but it is now dying out; its disappearance, like so many other native customs, appears to be coincident with the spread of "civilised " habits."

The novel figuaration presented here is a convulting and embryonic homage to Haddon and his transdisciplinary drive to make sense and make available, to journey with unfoxed destination.

String figures would seem to present an another means for drawing, an embodied and extended form of natural histrory illustration that seeks a means to representation beyond static images and pcitures, into the modeling of processes, and make sense of of morphology as matter of developmental dynamics, of formation rather than simply "final form."

It is a matter of "seeing with hands and talking without words," as historian of science Sabine Brauckmann has put it, one thinks also of Eva Hayward's "fingeryeyes," or of biologist Geerat Vermeij's simultaneously blind and all-seeing grasp on the shape of shelled life.